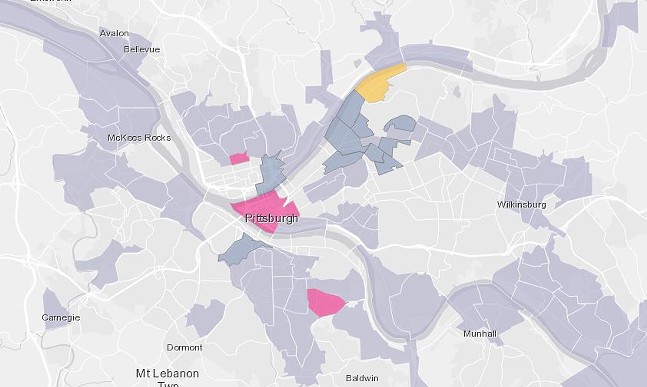

With 20 percent of its eligible census tracts being gentrified between 2000-2013, Pittsburgh was more gentrified than cities like San Francisco, Austin, and Denver. Gentrification is when redevelopment brings in more affluent residents, typically at the cost of displacing low-income people.

The national average for gentrification among eligible census tracts is about 9 percent, according to NCRC. The most gentrified city in the country

Pittsburgh’s gentrification might surprise some observers. To be on par with fast-growing cities like Portland, Ore. and Seattle could look unsettling considering Pittsburgh isn’t experiencing the same level of economic growth. And the exact Pittsburgh neighborhoods that experienced gentrification according to NCRC don’t match popular perceptions.

In Pittsburgh, those areas include Lawrenceville, Bloomfield, Garfield, Polish Hill, Downtown, and sections of the North Side and Mount Washington. According to NCRC, Pittsburgh experienced three neighborhoods with Black displacement: Downtown, the Mexican War Streets in North Side, and St. Clair.

For example, the study doesn’t list any census tracts in East Liberty as having experienced gentrification (in one tract average home prices actually went down from 2000-2010). The study also looked at displacement by race and East Liberty wasn’t included in the study’s Black displacement metric. (One East Liberty tract did lose more than 600 Black people between 2000-2010, but that was not large enough to qualify for displacement, by NCRC metrics.)

Jason Richardson, one of the study's authors, notes the likelihood that other neighborhoods, like East Liberty, could qualify for gentrification by NCRC metrics down the line, but he won’t know until data from 2013-2017 is released later this year. University of Pittsburgh economist Chris Briem has been documenting how some of the trends NCRC is studying have continued in East Liberty post-2013.

Richardson says NCRC adopted a methodology developed by Columbia University professor Lance Freeman, which is also utilized by the Philadelphia Federal Reserve. Richardson says neighborhoods that experience gentrification had sharp increases in average home values, residents with college attainment, and incomes.

He says many neighborhoods that gentrified contain service jobs staffed by low-income workers, who now can’t afford to live in those neighborhoods.

“We have to think about it from a social economic standpoint,” says Hogan. “Pittsburgh can’t figure out how to retain and build its local workforce. The further we push people out, I think that puts us at a disadvantage.”

Take Downtown. The neighborhood is home to thousands of high-paying jobs, but also plenty of service jobs at restaurants, retail stores, and bars. But Downtown is one of Pittsburgh’s most gentrified neighborhoods, with its average home prices tripling from $80,000 to $240,000 and its college attainment and average incomes doubling.

“That is a classic Downtown Rust Belt story,” says Richardson. “In most cities Pittsburgh’s size, we mostly see gentrification concentrated in the core.”

Hogan says part of this was an intentional effort to revitalize the neighborhood, as several developers were encouraged to create market-rate housing. Downtown affordable housing was preserved, but without a push to increase affordable units, many residents were forced out due to increases in the market-rate rents. Downtown lost 1,466 Black residents from 2000-2010.

For some neighborhoods included in the report, Hogan takes a more nuanced view.

“Are we really gentrifying, or are we diluting?” he asks. Hogan points out Deutschtown in the North Side, which lost mostly white residents as its home values and college attainment increased. But the average incomes there barely increased. A similar phenomenon played out in sections of Bloomfield.

Hogan says some of these changes were driven by Pittsburgh seeing an influx of college-educated millennials moving into historically white-working class neighborhoods, even though many of those millennials were still working low-wage jobs. Pittsburgh went from having one of the oldest average populations to the youngest over the same time span studied in the NCRC report. The home values increased possibly because many residential properties were remodeled and flipped.

But Hogan does see cases of “clear gentrification.” Lower Lawrenceville saw its average incomes increase by 25 percent, its college attainment double to 30 percent of residents and its average home values increase by 126 percent to $133,600. Other sections of Lawrenceville were also classified as

“That gentrification was driven by the changes of Butler Street. And I think it is amenities and the main street development stuff. And the flipping that started," says Hogan, referring to home flipping or residential redevelopment.

Hogan adds the study shows how gentrification has hurt both white and Black Pittsburghers. Upper Lawrenceville experienced a threefold increase in college attainment, a 20 percent increase in average income and a modest increase in average home values. Except Upper Lawrenceville was one of the few census tracts in America to experience white displacement. The area lost 740 white people and added about 440 Black people.So we are not DC (yet?) but Pittsburgh pretty high in the proportion of census tracts gentrified per this study (https://t.co/RWGzbsMmq1) pic.twitter.com/Lxu8Ch54E7

— chris briem (@chrisbriem) March 19, 2019

Hogan says Upper Lawrenceville, a historically white neighborhood, could be where many young Black residents working at tech companies are moving.

While gentrification is typically associated with the displacement of historically Black neighborhoods, Hogan says poverty, regardless of race, is the driving factor.

Hogan says this report should act as a clarion call to the city and regional leaders. He is encouraged by efforts like Community Land Trusts and inclusionary zoning in Lawrenceville. Pittsburgh City Councilor’s Deb Gross (D-Highland Park) recently introduced legislation calling inclusionary zoning in Lawrenceville, which would force new developments to include some affordable units.

But Hogan says broader and bolder changes need to be seriously considered, including big policies championed by Pittsburgh Mayor Bill Peduto.

“The city really needs to and the mayor needs to talk about housing policy,” says Hogan.